A couple of weeks ago, I likened ivermectin to acupuncture. The reason why the comparison came to me is because the reaction of those promoting ivermectin as a highly effective treatment—miracle cure, even—for COVID-19 is the same approach to evidence demonstrated by advocates of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM)—or, as it’s now called, “integrative medicine” or “integrative health”—and especially by acupuncture advocates. Specifically, as more and more high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials has failed to find a therapeutic effect from using ivermectin to treat COVID-19, increasingly its advocates point to positive studies that are less rigorous, such as observational and uncontrolled clinical studies. This is, more or less, exactly what acupuncture advocates have been doing as more and more high-quality studies with appropriate sham acupuncture placebo groups fail to find a detectable benefit for acupuncture for treating anything. They’ve been citing lower quality “pragmatic” studies, which might not be blinded (much less double-blinded), placebo-controlled, or, in some cases, even randomized. As I explain time and time again, though, citing pragmatic studies is putting the cart before the horse. Pragmatic studies are intended to see how well a treatment that’s been shown to work in high quality randomized controlled clinical trials works “out in the wild” outside of clinical trials and all the rigid protocols and selection criteria, a situation where the indications for the treatment inevitably expand as well. Ivermectin advocates even use the same sorts of excuses, too, when randomized controlled trials (RCTs) fail to show a benefit when ivermectin is used to treat COVID-19, such as claiming that medicine is biased and there is a double standard. (There is a double standard, but it doesn’t favor what acupuncture and ivermectin advocates think it does.)

In my post two weeks ago, I briefly mentioned an RCT of ivermectin for COVID-19 that was very much negative, but I didn’t discuss it extensively because it had not yet been published and had only been publicized in a news report from The Wall Street Journal. It turns out that last Thursday the study was finally published, in The New England Journal of Medicine, and, as described, it was a resoundingly negative trial, without even a hint of a whiff of efficacy. Was it a perfect trial? Of course not. No trial is. It was, however, large and well-designed and showed zero detectable effect from the early treatment of COVID-19 with ivermectin on hospitalizations and emergency room monitoring. As such, it was just one more drop in the drip-drip-drip of negative RCTs for ivermectin. Along with the drip-drip-drip of evidence that the most famous and largest RCTs of ivermectin for COVID-19 were either incompetently carried out or even fraudulent, and, as I mentioned, ivermectin for COVID-19 is looking increasingly like acupuncture for, well, anything.

So why bring this up again so soon after writing about it? I started thinking (always a dangerous thing) about science-based medicine (SBM) and the very purpose of this blog, and it occurred to me that the case of ivermectin is a very good real-world example of the utility of SBM and why evidence-based medicine (EBM) can fail for so long in a case like that of this particular drug.

Let’s go way, way back to the beginning, to explain the differences between EBM and SBM. Then I’ll explain how these differences apply. The primary difference is that SBM takes into account prior probability of a treatment working in evaluating clinical evidence.

SBM versus EBM

In the very first post ever on this blog all those years ago, SBM founder Dr. Steven Novella wrote:

All of science describes the same reality, and therefore it must (if it is functioning properly) all be mutually compatible. Collectively, science builds one cumulative model of the natural world. This means we can make rational judgments about what is likely to be true based upon what is already well established. This does not necessarily equate to rejecting new ideas out-of-hand, but rather to adjusting the threshold of evidence required to establish a new claim based upon the prior scientific plausibility of the new claim. Failure to do so leads to conclusions and recommendations that are not reliable, and therefore medical practices that are not reliably safe and effective.

This is why the authors of this blog strongly advocate for science-based medicine – the use of the best scientific evidence available, in the light of our cumulative scientific knowledge from all relevant disciplines, in evaluating health claims, practices, and products.

What did Steve mean by “prior scientific plausibility”? In brief, it’s an estimate of how likely a proposed treatment, when tested in an RCT or other clinical study, is likely to produce a positive result; i.e., a result consistent with the treatment “working” for the indication against which it is being tested. More specifically, it is an estimate of the prior probability of a given hypothesis before a study is conducted (in the case of an RCT that the null hypothesis will be rejected and there will be a statistically significant difference between the treatment group and the placebo group, indicating that the treatment works). I realize that this is boiling it down a bit, but I am writing for a lay audience.

It turns out that clinical trials are imperfect and can have a lot of “noise” even when designed and carried out perfectly. It also turns out that, from a Bayesian perspective, the prior plausibility that a treatment works matters a lot in interpreting clinical trial results; i.e., “posterior probability” the probability that a “positive result” is a “true positive” depends on the prior plausibility. (I’ll explain more in the next section what I mean by that.) Of course, in 2008, the original intent of SBM was to look at the evidence for treatments advocated as part of “alternative medicine”, CAM, or, as CAM is now more frequently called, “integrative medicine” or “integrative health”, both modalities in which “alternative medicine” (i.e., quackery) is “integrated” into conventional EBM. As I’ve argued, the newer names for CAM involving “integration” are nothing more than a rebranding of quackery.

Over the years, we’ve discussed many examples of alternative medicine with very low prior plausibility. Our favorite, as you might imagine, is homeopathy. The reason is simple. Based on homeopathy’s Law of Infinitesimals, which states states that the more you dilute a homeopathic remedy, the stronger it gets, we know that most homeopathic remedies are diluted to the point that it is unlikely that a single molecule of the original remedy is left. Homeopathy is thus arguably the purest example of a treatment with zero prior plausibility, given that most homeopathic remedies are is either water or another diluent. After all, as I like to say, for homeopathy to “work” for any disease or medical condition, several well-established laws of physics and chemistry would have to be not just wrong, but spectacularly wrong. It is, of course, true that there are other alternative medicine treatments that have a similar level of implausibility—impossibility, really—based on basic science considerations. (“Energy healing” comes to mind first.) However, homeopathy is so common and ubiquitous that it makes an excellent teaching example, which is why I use it so often. Also, I’ve noticed that a lot of people don’t even know what homeopathy is, including medical students and physicians. Many seem to think that homeopathy is just another form of herbal medicine. In any event, because many homeopathy remedies are just water used to make sugar pills, homeopathy is an excellent way to test the “noise” in clinical trials because it’s basically testing placebo vs. placebo.

So how does one consider prior plausibility in RCTs?

SBM vs. EBM: Prior probability/plausibility

We’ve long discussed the differences between EBM, which uses frequentist statistics, and SBM, which uses Bayesian reasoning that incorporates an estimate of prior plausibility

I’ve long complained about “methodolatry” in EBM, defined as the obscene worship of the RCT as the only valid method of investigation in medicine. It’s a term that I first learned in the context of countering misinformation about the H1N1 influenza vaccine back in 2009, taught to me by a senior epidemiologist. There’s a lot of methodolatry in EBM, and it’s part of the reason why treatments like acupuncture (whose prior plausibility, based on its pre-scientific concepts and mechanism of action is very, very low, albeit probably not zero) keep showing up as potentially working—or at least “needing more study”—to EBM practitioners. I would also like to take this opportunity right here to quote SBM co-founder and former regular Dr. Kimball Atwood, who discussed why EBM and SBM ought to be synonymous (but currently are not) and, more importantly why EBM is incomplete, and SBM is intended to complete it, or at least to fill in its “blind spot”. As Dr. Atwood put it, EBM “should not be without consideration of prior probability, laws of physics, or plain common sense” and “SBM and EBM should not only be mutually inclusive, they should be synonymous”.

Elsewhere, he argued:

That discussion made the point that EBM favors equivocal clinical trial data over basic science, even if the latter is both firmly established and refutes the clinical claim. It suggested that this failure in calculus is not an indictment of EBM’s originators, but rather was an understandable lapse on their part: it never occurred to them, even as recently as 1990, that EBM would soon be asked to judge contests pitting low powered, bias-prone clinical investigations and reviews against facts of nature elucidated by voluminous and rigorous experimentation. Thus although EBM correctly recognizes that basic science is an insufficient basis for determining the safety and effectiveness of a new medical treatment, it overlooks its necessary place in that exercise.

You can see where I’m going with this, I hope. In the post from which I drew that quote above, Dr. Atwood explained in more detail what I’m talking about in terms of Bayesian theory. It also discusses how an estimate of prior probability affects the posterior probability that a given p-value in a clinical trial indicates a “true” result, or, as Steven Goodman and Sander Greenland put it in 2007 put it, the “prior probability” of a hypothesis is its probability before the study, and the “posterior probability” is its probability after the study.

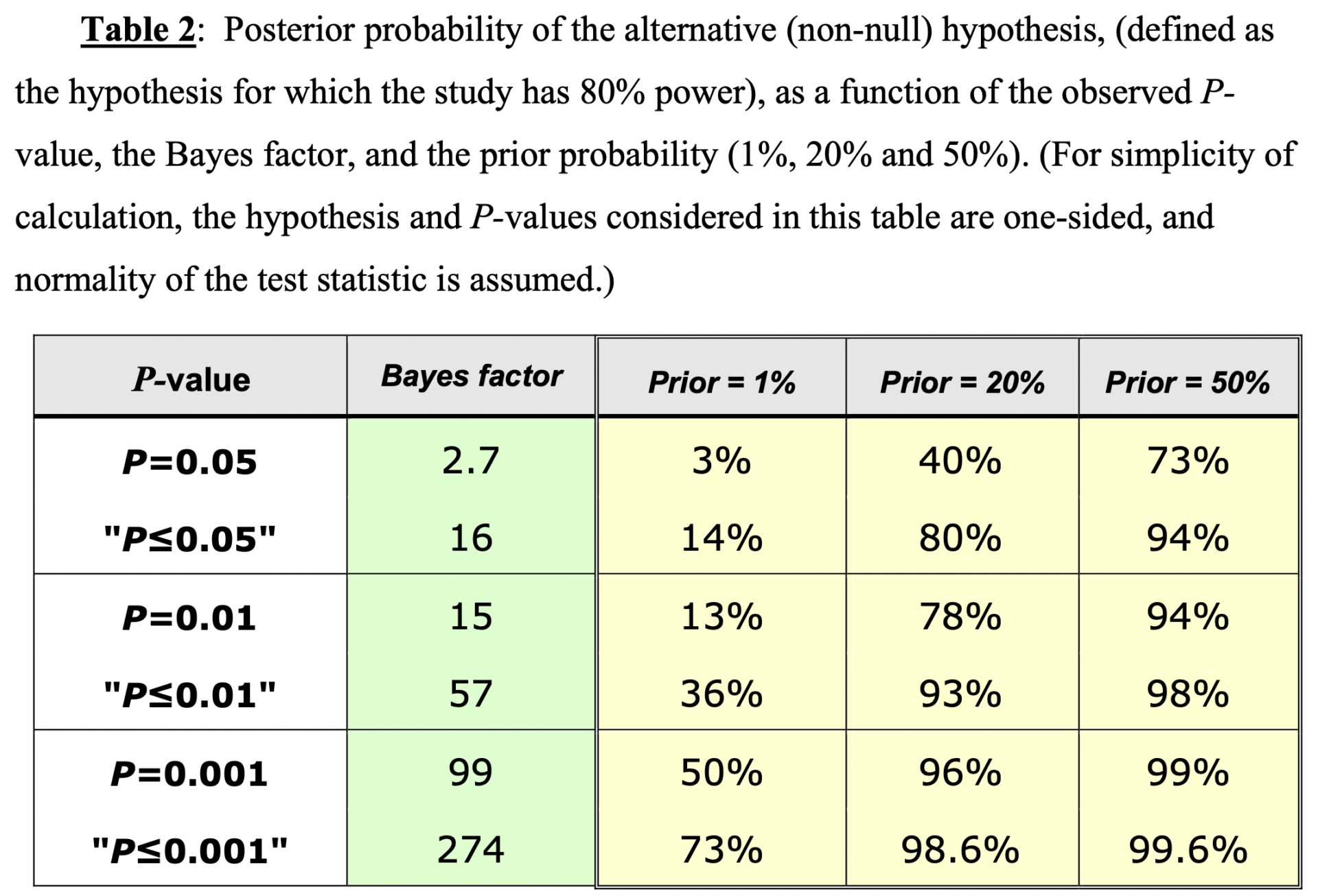

In fact, I think I’ll insert here a table that we at SBM like to cite to illustrate:

Goodman and Greenland’s 2007 calculation for posterior probability based on prior probability.

This is Table 2 from the 2007 article by Goodman and Greenland that illustrates how prior probability affects posterior probability for given p-values. Notice one thing. The lower the prior probability, the much lower the posterior probability for a given p-value, such that if a prior probability is estimated to be 1%, then the posterior probability of a result for a standard p-value less than or equal to 0.05 is only 14%, meaning that it’s only ~14% likely that the result is not a false positive under the conditions specified, which are commonly used conditions in designing RCTs. Even results with fairly low p-values bear serious questioning in the case of a treatment with a very low prior probability/plausibility. (For those of you who are more knowledgeable, the mathematical formulas and reasoning used to derive these numbers are in the reference.)

For something like homeopathy, in which the prior probability based on its scientific impossibility under currently understood science is zero, the situation is, of course, far worse than in the table above. I will also quote Steve Novella and myself from a 2014 paper that we coauthored, in order to address a common criticism of our argument that RCTs of highly improbable/implausible treatments (like homeopathy) are akin to testing whether magic works as medicine:

It should also be noted that ‘biologically plausible’ does not mean ‘knowing the exact mechanism’. What it does mean is that the mechanism should not be so scientifically implausible as to be reasonably considered impossible. In other words, the mechanism should not violate laws and theories in science that rest on far sturdier and longer established foundations than imperfect, bias-prone clinical trials. For example, homeopathy violates multiple laws of physics with its claims that dilution can make a homeopathic remedy stronger and that water can retain the ‘memory’ of substances with which it has been in contact before [9]. Thus, treatments like homeopathy should be dismissed as ineffective on basic scientific grounds alone. That is why we propose the term science-based medicine (SBM) as opposed to evidence-based medicine (EBM). SBM restores basic science considerations to EBM and is what EBM should be.

I’m assuming that most SBM readers accept that, for example, homeopathy or energy healing is so incredibly implausible/improbable from basic science considerations alone that basic science is all that is needed to reject it as a treatment. I’m also assuming that most SBM readers will accept that, for example, acupuncture, although not as improbable/implausible as homeopathy, is still incredibly implausible, with a prior probability reasonably estimated as very much less than 1%. (I’d say very much less than 0.0001%, even.) I’ll also emphasize right here that, while basic science alone can in the cases under discussion here be enough to reject a proposed therapy as so implausible as to be impossible and not worth testing in RCTs, basic science is never enough to demonstrate that a treatment works, no matter how plausible the mechanism and compelling the preclinical data in cell culture and animals. Many are the treatments that appeared highly promising before being tested in humans, only to fail.

But what about ivermectin for COVID-19? That doesn’t fall into the same categories as homeopathy or acupuncture, does it? It’s an actual drug that is highly effective against diseases caused by roundworm infestations. Its discoverers even won the Nobel Prize for that indication! Is it so implausible that ivermectin might also work against a viral illness like COVID-19? There was even a proposed mechanism for its antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. That mechanism was even based on in vitro cell culture studies!

All of these are reasonable considerations. So join me as I discuss them in the last two sections of this post, in which I hope to convince you that the prior probability for ivermectin was always very, very low—not homeopathy-level low, admittedly, but quite low.

Ivermectin vs. SBM: Back to the future

So how did the idea come about that ivermectin might be an effective treatment for COVID-19 anyway? You might remember how the idea that repurposing hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug with immune modulating properties that make it useful as a mild immunosuppressive drug to use to treat autoimmune diseases, took hold early in the pandemic. In brief, Chinese physicians in Wuhan reported in early 2020 that none of a group of 80 patients with lupus erythematosus who were taking hydroxychloroquine went on to catch COVID-19. (Never mind that immunosuppressed patients were exactly the patients most likely to assiduously follow the recommendations of public health authorities during an epidemic.) A number of clinical trials were registered, and, based on anecdotal reports and small clinical trials (nearly all of which are as yet unpublished), in February the Chinese government published an expert consensus recommending CQ or HCQ for patients with COVID-19. Soon after, a number of nations followed suit. In addition, French scientist Didier Raoult started flogging hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19 and was soon joined by President Donald Trump and of course!—Dr. Mehmet Oz. The rest, unfortunately, is history. Even though by late summer 2020, it was becoming quite clear that hydroxychloroquine was ineffective against COVID-19, a conspiracy theory of a “suppressed cure” had been born.

The idea that ivermectin could be repurposed to treat COVID-19 is similar, but based on even less evidence. I discussed this evidence several months ago, when a conspiracy theory was being spread that Pfizer’s new antiviral drug Paxlovid was “Pfizermectin” because both ivermectin and Paxlovid have protease inhibition activity. I’ll just recap briefly.

It’s been known for years that ivermectin can inhibit coronavirus replication through the inhibition of a protein called α/β1 importin, something reported a decade ago. This particular protein is involved in the transport of proteins into the nucleus from the cytoplasm. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the transport of certain proteins into the nucleus is important for completion of its lifecycle. Now here’s the thing. Inhibition of this protein complex by ivermectin and preventing the replication of HIV and the Dengue virus requires fairly high concentrations (at least in terms of drug concentrations). The original Australian paper published in May 2020 that examined the ability of ivermectin to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication showed similar results, specifically the need for a very high concentration of drug to inhibit the importin that was needed for SARS-CoV-2 replication.

So what’s the problem? It’s basic pharmacology, as summarized in this review:

As noted, the activity of ivermectin in cell culture has not reproduced in mouse infection models against many of the viruses and has not been clinically proven either, in spite of ivermectin being available globally. This is likely related to the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic safety window for ivermectin. The blood levels of ivermectin at safe therapeutic doses are in the 20–80 ng/ml range [44], while the activity against SARS-CoV2 in cell culture is in the microgram range. Ivermectin is administered orally or topically. If safe formulations or analogs can be derived that can be administered to achieve therapeutic concentrations, ivermectin could be useful as a broad-spectrum antiviral agent.

Specifically, the IC50 (the concentration that produces 50% of maximal inhibition of a process) was in the 6 μM. Given that the molecular weight of ivermectin is 875 g/mol, 6 μM translates into ~5.25 mg/L or ~5.25 μg/ml, a concentration that is roughly 66-fold higher than the upper end of the range of blood levels of ivermectin safely achievable in a human’s bloodstream. Even this paper proposing ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19 notes this serious problem:

A dose of 12 mg twice daily alone or in combination with other therapy for 5–7 days has been proposed as a safe therapeutic option for mild, moderate or severe cases of Covid-19 infection.10 The time to reach maximum plasma concentration of 20–50 ng/ml, after a dose of 6 or 12 mg, respectively is approximately 4 h.

This is almost certainly the reason that ivermectin doesn’t work against COVID-19 in spite of its activity in vitro against SARS-CoV-2. It requires a concentration roughly 66- to 197-fold higher than is safely achievable in the blood. That’s why the review concluded that maybe an ivermectin analogue that is either more active or can achieve a higher concentration safely in the bloodstream is worth investigating. Based on the proposed mechanism in the Australian paper, ivermectin was never a good candidate as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2. As I discussed for the claim that ivermectin should be considered a promising drug for COVID-19 based on its protease inhibitor activity, the situation is just as bad. Again, based on in vitro results, ivermectin was never a promising candidate as an antiviral drug to treat COVID-19.

But how do we translate this into prior probability? In the discussion of the NEJM trial to which I linked above, someone suggested what is probably an accurate assessment:

Yup. As liked to say, it wasn't homeopathy-level implausibility, but it was highly implausible.

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) March 31, 2022

I think that a pretest probability of much less then 1% is accurate given in vitro results like the experiments that I described. I also noted on Thursday after seeing the NEJM study:

To accept that such a mechanism might be operative, the clinical trial results have to be highly compelling and pristine. None of the clinical trials for #ivermectin even came close to that standard.

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) March 31, 2022

In other words, if ivermectin were to be actually useful against COVID-19, it would almost certainly have to work by a different molecular mechanism than the one described in the in vitro study cited because it’s known to be impossible to safely achieve ivermectin concentrations in human blood that are sufficient even to inhibit viral replication by 50%—or even anywhere near such concentrations. Of course, it’s always possible that such a previously unknown mechanism was operative, but highly unlikely. Moreover, to consider that such a mechanism might be operative, the clinical trial results would have to be pristine in terms of very compelling results from very well-designed and executed clinical trials, or, as Steve Novella once put it, “When the basic science dictates that a proposed treatment is highly implausible, the bar for clinical evidence should be raised proportionately”.

This never applied to any clinical trial of ivermectin for COVID-19, not even the seemingly strongly “positive” ones, and that’s even leaving aside the discovered incompetence and likely fraud in the largest “positive” trials, which led to falsely “positive” meta-analyses.

As I said, these negative results never surprised those of us with SBM tendencies. Given the very low prior probability that ivermectin is effective against COVID-19 based on in vitro data, even the best “positive” clinical trials likely had a low posterior probability. Moreover, they weren’t the only trials. Most trials were equivocal or negative, and, as is the case with acupuncture, the larger and better designed the study, the more likely it was to be negative, which leads me to an adage that I frequently use on Twitter (because it’s pithy) but have not yet (as far as I can recall) repeated here on SBM:

Very low prior plausibility

+

Equivocal clinical studies

=

Drug doesn’t work for the proposed indication

Or at least, any effect observed will be too small and inconsistent to be clinically useful.

SBM: It’s not just for CAM anymore. (It never was.)

It’s been a long time since we’ve discussed the difference between EBM and SBM in quite this much detail, discussions like this having been common here around 2008-2010, but I felt that a discussion like this was overdue. The reason, of course, has been the pandemic and how EBM has treated highly implausible COVID-19 therapies in the same way that it’s long treated highly implausible CAM therapies, through the lens of methodolatry, in which only RCTs matter for determining if a treatment does or doesn’t work and in which even flawed RCTs trump basic science—except that they don’t, at least when Bayesian considerations are used.

What makes the discussion of ivermectin interesting to me in this context is that it is an example of why SBM matters in all areas of medicine, not just the consideration of “integrative” quackery. SBM mavens all immediately realized that, even if you accepted the rationale proposed at face value, ivermectin was incredibly implausible as an effective therapy for COVID-19 just based on the in vitro data alone. It’s basic pharmacology. A drug that only inhibits the target protein at a concentration that is at least nearly 70-fold higher than the highest blood concentration of drug that can be safely achieved using standard dosing is incredibly unlikely to be an effective treatment. It’s also a general principle that most highly effective drugs inhibit their target at nanomolar or ng/ml concentrations, not micromolar or μg/ml concentrations. Candidate drugs that only inhibit their target at such high concentrations, in general, tend to be incredibly unlikely to be useful drugs.

Indeed, any pharmaceutical company that developed a drug just like ivermectin for COVID-19 would have abandoned it after in vitro testing showing that it required such a high concentration to inhibit the intended target. A drug company would have deemed such a candidate compound as not worth pursuing further, except maybe as a base molecule to chemically modify so that it either inhibits the desired target at a much lower concentration or becomes able to achieve much higher blood levels safely. Yet a number of scientists whom I respect were, until very recently, saying that ivermectin “probably doesn’t work” or even saying that there was a strong developing evidence base; that is, until it all fell apart with the determinations that a couple of the largest, most “positive” studies couldn’t possibly have been carried out as reported. Basic pharmacology matters.

I also realize that ivermectin believers won’t accept an SBM-based argument against ivermectin any more than believers in acupuncture or homeopathy accept SBM-based Bayesian arguments against their favorite woo. Indeed, in reaction to the NEJM study, there were a lot of reactions like this:

Effect of Early Treatment with Ivermectin among Patients with Covid-19 | NEJM, FAKE NEWS https://t.co/fMxY0LYuQN

— skp (@pt34tide) April 1, 2022

And this:

All of them fell under the sorts of “rationales” as in this meme, which I most definitely am stealing:

I'm stealing that meme. pic.twitter.com/dthJgAAKR8

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) March 31, 2022

However, remember that EBM arguments don’t sway believers in homeopathy or acupuncture, either; so one should not expect that EBM or SBM arguments would sway ivermectin believers. My hope is that SBM thinking will be more likely to sway EBM adherents who don’t really take into account prior plausibility in evaluating RCT evidence and therefore take much longer to reach a conclusion that is obvious to SBM about a treatment, in the case of ivermectin that it doesn’t work against COVID-19. Indeed, at this stage I would argue that it is unethical to begin another RCT of ivermectin to treat COVID-19. Given how resoundingly negative the evidence is now, such a trial would be all risk with no realistic potential for any patient to benefit. I’m not even sure whether it’s ethical to continue to recruit patients to RCTs of ivermectin still enrolling.

In future talks about the differences between SBM and EBM and how EBM should be (but still is not) synonymous with SBM, I plan on adding the example of ivermectin for COVID-19 to my long-used examples of homeopathy and acupuncture when I discuss Bayesian thinking and prior probability/plausibility because SBM isn’t just for CAM any more. It never was, and never should have been. If I’ve been guilty of not applying it to conventional medicine as much as I do to CAM, the case of ivermectin has shown me the error of my ways.